Let’s start with transforming the code we introduced in the previous chapter into a parallel version.

C++17 parallel algorithms¶

C++17 introduced parallel algorithms using execution policies. So, let’s see if we can use it to run our exiting code in parallel.

Let’s first include the necessary headers and function templates for different output formats:

#include <iostream> // <-- std::cout and std::endl

#include <iomanip> // <-- std::setw()

#include <vector> // <-- std::vector

#include <random> // <-- std::t19937 and std::uniform_int_distribution

#include <algorithm> // <-- std::generate() and std::generate_n()

#include <execution> // <-- std::execution::par

#include <g3p/gnuplot> // <-- g3p::gnuplot

// load the Threading Building Blocks library that under the hood

// does the actual parallelization

#pragma cling load("libtbb.so.2")

// function template to print the numbers

template <typename RandomIterator>

void print_numbers(RandomIterator first, RandomIterator last)

{ auto n = std::distance(first, last);

for (size_t i = 0; i < n; ++i)

{ if (0 == i % 10)

std::cout << '\n';

std::cout << std::setw(3) << *(first + i);

}

std::cout << '\n' << std::endl;

}

// function template to render two randograms side-by-side

template<typename Gnuplot, typename RandomIterator>

void randogram2

( const Gnuplot& gp

, RandomIterator first

, RandomIterator second

, size_t width = 200

, size_t height = 200

)

{ gp ("set term pngcairo size %d,%d", width * 2, height)

("set multiplot layout 1,2")

("unset key; unset colorbox; unset tics")

("set border lc '#333333'")

("set margins 0,0,0,0")

("set bmargin 0; set lmargin 0; set rmargin 0; set tmargin 0")

("set origin 0,0")

("set size 0.5,1")

("set xrange [0:%d]", width)

("set yrange [0:%d]", height)

("plot '-' u 1:2:3:4:5 w rgbimage");

for (size_t i = 0; i < width; ++i)

for (size_t j = 0; j < height; ++j)

{ int c = *first++;

gp << i << j << c << c << c << "\n";

}

gp.end() << "plot '-' u 1:2:3:4:5 w rgbimage\n";

for (size_t i = 0; i < width; ++i)

for (size_t j = 0; j < height; ++j)

{ int c = *second++;

gp << i << j << c << c << c << "\n";

}

gp.end() << "unset multiplot\n";

display(gp, false);

}1st attempt¶

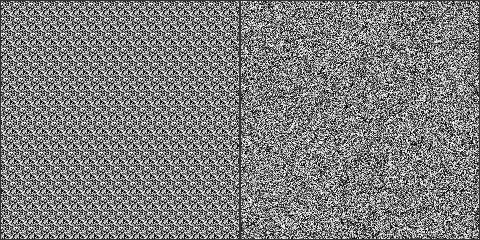

Because C++11 random engines are not thread safe, to prevent data race accessing our engine, we pass a copy of the engine rather than reference and see what happens. Here’s our first attempt side-by-side with the serial code and the resulting randograms for the comparisons:

const unsigned long seed{2718281828};

const auto n{100};

std::vector<int> v(n);

std::mt19937 r(seed);

std::uniform_int_distribution<int> u(10, 100);

std::generate_n

( std::execution::par

, std::begin(v)

, n

, std::bind(u, r) // <-- copy of r

);

print_numbers(std::begin(v), std::end(v));

35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35

35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35

35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35

35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35

35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35

35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35

35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35

35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35

35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35

35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35 35

const unsigned long seed{2718281828};

const auto n{100};

std::vector<int> v(n);

std::mt19937 r(seed);

std::uniform_int_distribution<int> u(10, 100);

std::generate_n

(

std::begin(v)

, n

, std::bind(u, std::ref(r))

);

print_numbers(std::begin(v), std::end(v));

35 92 81 73 80 22 78 71 25 66

66 12 96 35 30 26 68 76 68 63

63 29 13 65 36 37 98100 63 47

85 12 50 90 84 47 43 15 78 92

17 42 98 22 67 43 65 92 55 92

70 94 28 26 31 69 91 37 57 25

91 14 18 20 14 25 20 91 51 56

75 53 83 73 29 86 51 94 13 11

42 88 88 55 94 11 13 81 12 18

35 74 31 74 25 77 36 96 23 32

const size_t w{240}, h{240}, n{w * h};

std::vector<int> parallel(n), serial(n);

std::mt19937 pr(seed), sr(seed); // start with the same seed

std::uniform_int_distribution<int> c(0, 255); // for rgb

// parallel version passing copy of the engine

std::generate_n(std::execution::par

, std::begin(parallel), n, std::bind(c, pr));

std::generate_n(std::begin(serial), n, std::bind(c, std::ref(sr)));

// our gnuplot instance

g3p::gnuplot gp;

// rendering two randograms side-by-side for comparison

randogram2(gp, std::begin(parallel), std::begin(serial), w, h);

Not quite the output we’ve expected but if you think about it, that was obvious. By using a copy of the engine, each thread initiates with a new instance of the engine and restarts with the same number in the sequence, producing a repeating pattern as you can see in the left randogram.

2nd attempt¶

Let’s forget about the data race possibility for a moment and pass a reference to the engine, exactly like the way we did for the serial version, to see if that solves the problem. Here’s our second attempt in the same format:

const unsigned long seed{2718281828};

const auto n{100};

std::vector<int> v(n);

std::mt19937 r(seed);

std::uniform_int_distribution<int> u(10, 100);

std::generate_n

( std::execution::par

, std::begin(v)

, n

, std::bind(u, std::ref(r)) // <-- reference of r

);

print_numbers(std::begin(v), std::end(v));

32 96 23 25 77 36 12 18 35 74

31 74 86 51 94 13 11 42 88 88

55 94 11 13 81 70 94 28 26 31

69 91 37 57 25 91 14 18 20 14

25 20 91 51 56 75 53 83 73 29

35 92 81 73 80 22 78 71 25 66

66 12 96 35 30 26 68 76 68 63

63 29 13 65 36 37 98100 63 47

85 12 50 90 84 47 43 15 78 92

17 42 98 22 67 43 65 92 55 92

const unsigned long seed{2718281828};

const auto n{100};

std::vector<int> v(n);

std::mt19937 r(seed);

std::uniform_int_distribution<int> u(10, 100);

std::generate_n

(

std::begin(v)

, n

, std::bind(u, std::ref(r))

);

print_numbers(std::begin(v), std::end(v));

35 92 81 73 80 22 78 71 25 66

66 12 96 35 30 26 68 76 68 63

63 29 13 65 36 37 98100 63 47

85 12 50 90 84 47 43 15 78 92

17 42 98 22 67 43 65 92 55 92

70 94 28 26 31 69 91 37 57 25

91 14 18 20 14 25 20 91 51 56

75 53 83 73 29 86 51 94 13 11

42 88 88 55 94 11 13 81 12 18

35 74 31 74 25 77 36 96 23 32

const size_t w{240}, h{240}, n{w * h};

std::vector<int> parallel(n), serial(n);

std::mt19937 pr(seed), sr(seed); // start with the same seed

std::uniform_int_distribution<int> c(0, 255); // rgb values (0-255)

// parallel version passing reference of the engine

std::generate_n(std::execution::par,

std::begin(parallel), n, std::bind(c, std::ref(pr)));

// serial version

std::generate_n(std::begin(serial), n, std::bind(c, std::ref(sr)));

// rendering two randograms side-by-side for comparison

randogram2(gp, std::begin(parallel), std::begin(serial), w, h);

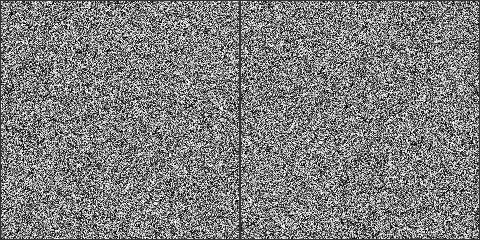

At first glance, judging by the the short output from the first two tabs, it seems without much efforts we hit the jackpot. But that’s because we only generated 100 random numbers. So, there’s a chance you get the exact same result as the serial version, even by repeating several times.

But as you can see in the generated randograms, the parallel version on the left is different from the serial version on the right, despite using the same seed for both. The parallel version generates similar but different sequence of numbers.

But that’s not the actual problem. The real problem is that the parallel version is even slower than the serial version! Let’s first increase the number of random numbers and then time them:

const size_t n = 1'000'000;

serial.resize(n);

parallel.resize(n);%%timeit

std::generate_n

(

std::begin(serial)

, n

, std::bind(u, std::ref(sr))

);75.4 ms +- 10.2 ms per loop (mean +- std. dev. of 7 runs 10 loops each)

%%timeit

std::generate_n

( std::execution::par

, std::begin(parallel)

, n

, std::bind(u, std::ref(pr))

);66.6 ms +- 14.6 ms per loop (mean +- std. dev. of 7 runs 10 loops each)

That proves we need better strategies to generate random numbers in parallel and that’s the subject of the next section.

Parallel random numbers, the right way¶

Below you can find four proven methods to introduce parallelism into ARNGs. These are general techniques that can be used equally well in shared memory, distributed memory and heterogenous setups.

1️⃣ Random seeding

All parallel threads use the same engine but a different random seed.

✅ Good scaling

🔻 Possible correlations in subseqs

🔻 Overlapping of subseqs

🔻 Cannot play fair

2️⃣ Parametrization

All parallel threads use the same engine but different parameters for each thread.

✅ No overlapping

🔻 Multiple streams must be supported

🔻 Possible correlations in streams

🔻 Cannot play fair

3️⃣ Block splitting

Each block in the sequence is generated by a different thread.

✅ No overlapping

✅ No correlations

✅ Plays fair

🔻 Need jump-ahead support

🔻 Shortened period

🔻 Need modified generate()

4️⃣ Leapfrog

Consecutive random numbers are generated by different threads.

✅ No overlapping

✅ No correlations

✅ Plays fair

🔻 Need jump-ahead support

🔻 Shortened period

🔻 Need modified generate()

🔻 Prone to false sharing on CPU

Random seeding¶

In random seeding, all parallel threads use the same engine but a different random seed. One way to do this is to use the thread numbers as seed. Unfortunately, there’s no provisions in C++11’s concurrency library to get the thread numbers. So, we have to hash the thread IDs instead and use them to seed the instantiated thread-local engines. That means we get completely different sequence of random numbers on each invocation.

#include <thread> // <-- std::hash and std::thread

const unsigned long seed{2718281828};

const auto n{100};

std::vector<int> v(n);

std::mt19937 r(seed);

std::uniform_int_distribution<int> u(10, 99);

std::hash<std::thread::id> hasher;

std::generate_n

( std::execution::par

, std::begin(v)

, n

, [&]()

{ thread_local std::mt19937 r(hasher(std::this_thread::get_id()));

return u(r);

}

);

print_numbers(std::begin(v), std::end(v));

93 79 19 34 52 80 60 58 82 71

27 17 24 89 18 72 35 49 86 15

26 36 22 80 17 80 53 18 33 10

25 82 26 93 83 40 59 97 12 21

93 66 56 32 53 98 10 42 50 59

82 37 31 99 34 36 68 40 59 32

56 12 64 45 72 25 80 43 49 39

45 31 72 31 46 40 62 17 50 66

32 18 29 51 35 31 75 67 20 40

92 49 59 85 49 94 51 51 68 64

//

const unsigned long seed{2718281828};

const auto n{100};

std::vector<int> v(n);

std::mt19937 r(seed);

std::uniform_int_distribution<int> u(10, 99);

std::generate_n

(

std::begin(v)

, n

, std::bind(u, std::ref(r))

);

print_numbers(std::begin(v), std::end(v));

34 91 80 72 79 21 77 70 25 65

66 12 95 35 30 26 68 75 67 63

63 29 13 64 36 37 97 99 62 47

85 12 49 90 83 46 43 15 77 91

17 41 97 22 67 42 64 91 54 91

69 93 28 26 31 69 90 37 56 25

90 14 18 20 14 25 20 90 51 55

74 52 82 72 29 85 51 93 13 11

42 87 87 54 93 11 13 80 12 18

35 73 31 73 25 76 36 96 23 32

const size_t w{240}, h{240}, n{w * h};

std::vector<int> parallel(n), serial(n);

std::mt19937 pr(seed), sr(seed); // start with the same seed

std::uniform_int_distribution<int> c(0, 255); // rgb values (0-255)

// random seeding

std::generate_n

( std::execution::par

, std::begin(parallel)

, n

, [&]()

{ thread_local std::mt19937 pr(hasher(std::this_thread::get_id()));

return c(pr);

} );

// serial version

std::generate_n(std::begin(serial), n, std::bind(c, std::ref(sr)));

// rendering two randograms side-by-side for comparison

randogram2(gp, std::begin(parallel), std::begin(serial), w, h);

Parametrization¶

In parametrization, all parallel threads use the same type of generator but with different parameters for each thread. For example, LCG generators support an additive constant for switching to another stream, so called multiple streams. So, no overlapping occurs but there’s a chance of correlations between streams. Like random seeding, generates different sequence of random numbers on each run. As std::mt19937 doesn’t support multiple streams, we’ll switch to the pcg32 generator provided by the Ranx library.

#include <ranx/pcg/pcg_random.hpp> // <-- pcg32

const unsigned long seed{2718281828};

const auto n{100};

std::vector<int> v(n);

std::uniform_int_distribution<int> u(10, 99);

std::hash<std::thread::id> hasher;

std::generate_n

( std::execution::par

, std::begin(v)

, n

, [&]()

{ thread_local pcg32 r(seed, hasher(std::this_thread::get_id()));

return u(r);

}

);

print_numbers(std::begin(v), std::end(v));

56 83 91 55 19 84 61 37 81 29

23 92 40 45 85 86 69 40 97 58

35 53 77 68 90 96 51 36 12 96

86 25 16 60 15 11 92 33 50 78

50 25 51 92 98 52 48 53 63 78

37 35 64 44 13 58 19 69 55 59

33 11 28 96 57 59 66 19 21 24

92 32 96 67 20 99 11 71 63 37

97 57 52 20 71 81 30 59 87 64

36 70 68 42 80 90 90 58 15 26

#include <thread> // <-- std::hash and std::thread

const unsigned long seed{2718281828};

const auto n{100};

std::vector<int> v(n);

std::mt19937 r(seed);

std::uniform_int_distribution<int> u(10, 99);

std::hash<std::thread::id> hasher;

std::generate_n

( std::execution::par

, std::begin(v)

, n

, [&]()

{ thread_local std::mt19937 r(hasher(std::this_thread::get_id()));

return u(r);

}

);

print_numbers(std::begin(v), std::end(v));

93 79 19 34 52 80 60 58 82 71

27 17 24 89 18 72 35 49 86 15

26 36 22 80 17 80 53 18 33 10

25 82 26 93 83 40 59 97 12 21

93 66 56 32 53 98 10 42 50 59

82 37 31 99 34 36 68 40 59 32

56 12 64 45 72 25 80 43 49 39

45 31 72 31 46 40 62 17 50 66

32 18 29 51 35 31 75 67 20 40

92 49 59 85 49 94 51 51 68 64

//

const unsigned long seed{2718281828};

const auto n{100};

std::vector<int> v(n);

std::mt19937 r(seed);

std::uniform_int_distribution<int> u(10, 99);

std::generate_n

(

std::begin(v)

, n

, std::bind(u, std::ref(r))

);

print_numbers(std::begin(v), std::end(v));

34 91 80 72 79 21 77 70 25 65

66 12 95 35 30 26 68 75 67 63

63 29 13 64 36 37 97 99 62 47

85 12 49 90 83 46 43 15 77 91

17 41 97 22 67 42 64 91 54 91

69 93 28 26 31 69 90 37 56 25

90 14 18 20 14 25 20 90 51 55

74 52 82 72 29 85 51 93 13 11

42 87 87 54 93 11 13 80 12 18

35 73 31 73 25 76 36 96 23 32

const size_t w{240}, h{240}, n{w * h};

std::vector<int> parallel(n), serial(n);

std::mt19937 sr(seed); // start with the same seed

std::uniform_int_distribution<int> c(0, 255); // rgb values (0-255)

// random seeding

std::generate_n

( std::execution::par

, std::begin(parallel)

, n

, [&]()

{ thread_local pcg32 r(seed, hasher(std::this_thread::get_id()));

return c(pr);

} );

// serial version

std::generate_n(std::begin(serial), n, std::bind(c, std::ref(sr)));

// rendering two randograms side-by-side for comparison

randogram2(gp, std::begin(parallel), std::begin(serial), w, h);

Block splitting¶

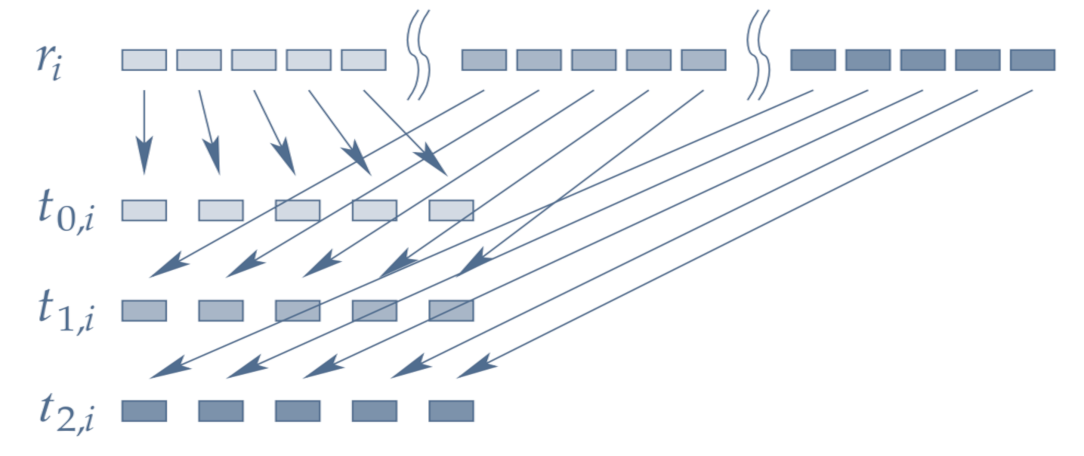

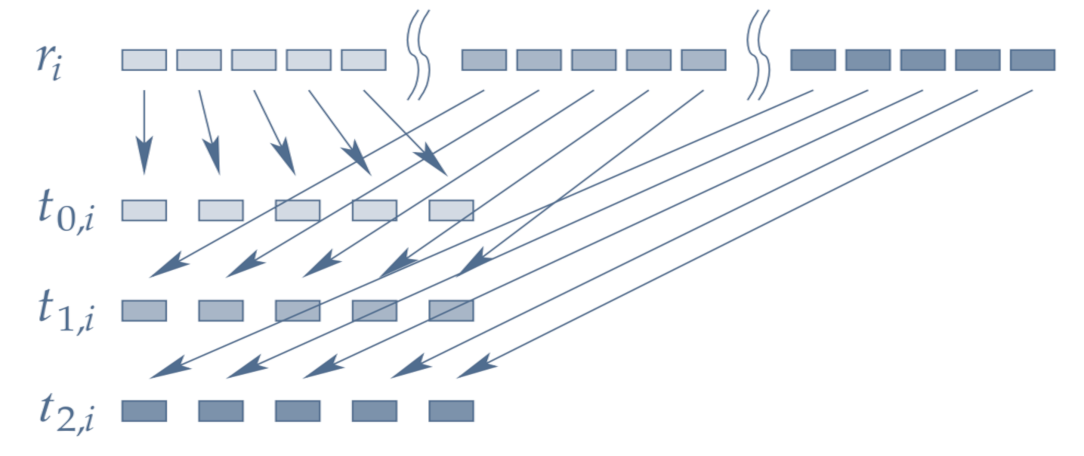

As shown in the following figure, in block splitting the sequence of an RNG is divided into equally-sized consecutive blocks that are generated by different threads:

Figure 1:Parallelization by block splitting (source: doc/trng.pdf )

This way, no overlapping or correlations occurs between streams at the expense of shortened period by a factor of number-of-threads. If the block size is larger than the cache line, which is usually the case for large data, no false sharing happens as well.

For threads to skip the block size, there should be an efficient way of jumping-ahead in the sequence which is supported by some engines, most notably LCGs generators. But that also requires a modified std::generate() to call the engine’s skipping function. To that end, we use the Ranx library, which provides both the engine (i.e. PCG family) and the alternatives to std::generate()/std::generate_n() functions that use block splitting for parallelization using OpenMP on CPUs.

If we match block splitting method by a distribution that doesn’t discard any values generated by the engine, then it can plays fair as well. The Ranx library includes the distributions provided by TRNG that can do that. We’ll cover that in the next chapter ».

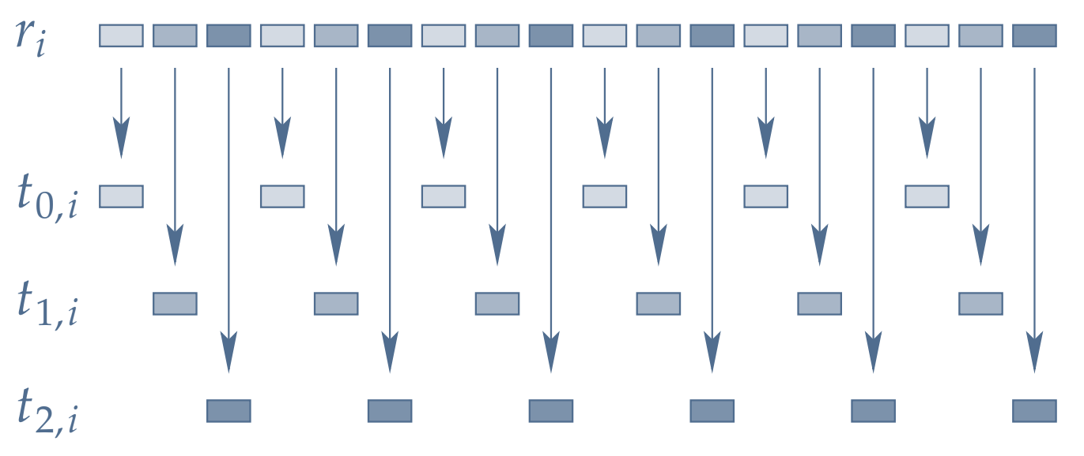

Leapfrog¶

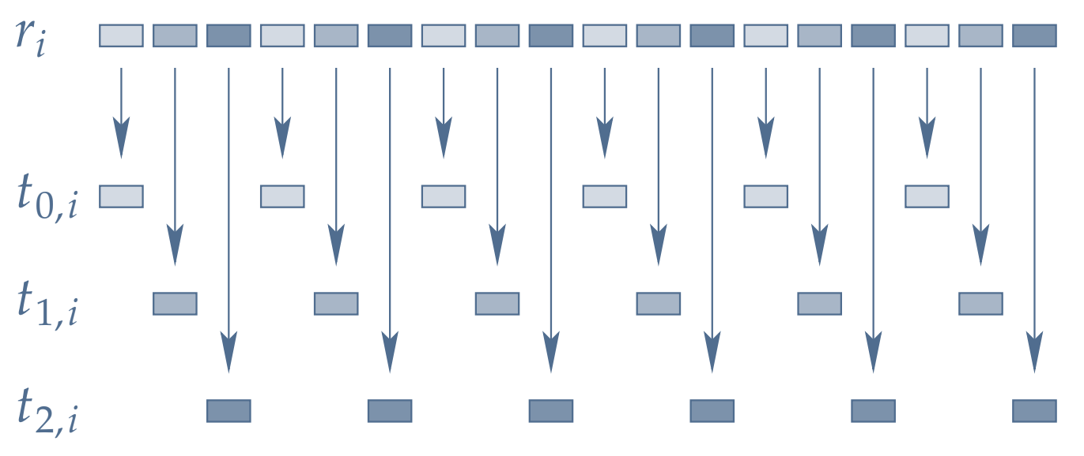

In leapfrog method, the consecutive random numbers are generated by different threads. As the values sitting next to each other on a cache line (Figure 2), are each generated by a different thread, it’s highly susceptible to false sharing on CPU but not as much on GPU.

Figure 2:Parallelization by leapfrogging (source: doc/trng.pdf )

The other pros and cons are exactly like the block splitting. The Ranx library relies on leapfrog method to generate the code on CUDA and ROCm platforms. We’ll cover that in the next chapter ».

Concluding remarks¶

In this chapter we investigated why dropping std::execution::par into otherwise-correct serial RNG code fails to deliver: passing a copy of the engine yields repeating patterns, passing reference to the engine creates races and nondeterminism, and even when it “works” it often runs slower. We then surveyed four established strategies for parallel RNG—random seeding, parametrization, block splitting, and leapfrogging—highlighting their trade‑offs.

These observations motivate the design behind Ranx: use block splitting on CPUs (OpenMP) and leapfrogging on GPUs (CUDA/ROCm/oneAPI), paired with distributions that avoid discarding values so results can play fair. Crucially, Ranx wraps the engine+distribution into a device‑compatible functor and applies jump‑ahead/stride patterns so that, given the same seed, you get reproducible sequences independent of thread count or backend.

In the next chapter, we’ll put this into practice: replacing std::generate(_n) with Ranx’s counterparts and using ranx::bind() to write code once and obtain identical outputs across OpenMP, CUDA, ROCm, and oneAPI.